Targeting Chronic Depression, Anxiety, Addiction, IBS, and Narcissism in Adults

Executive Summary

Mental Health Complexity: Mental health conditions like depression, anxiety, addiction, irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), and narcissism are multifactorial – arising from an interplay of neurobiological, psychological, social, and existential factors. Traditional single-modality treatments (medication-only or therapy-only) often address only part of the problem. An integrated framework is needed to encompass brain, mind, body, and existential meaning.

Integrated Framework: This report proposes a holistic model combining clinical neuroscience (brain structure/function), cognitive-behavioral strategies (thoughts and behaviors), psychodynamic insights (unconscious and developmental factors), existential psychology (meaning, purpose, authenticity), and somatic therapies (mind-body techniques). This integrated approach aligns with the World Health Organization’s view that mental health is determined by a complex interplay of biological and psychosocial factors and addresses the often neglected “meaning-dimension” of health.

Key Findings: Since 2000 (especially post-2010), research shows increasing convergence among disciplines:

- Neuroscience confirms that chronic stress and adverse experiences can re-wire brain circuits, contributing to mood and anxiety disorders. Effective psychotherapy and behavioral interventions can induce positive neuroplastic changes, normalizing overactive fear centers (amygdala) and strengthening prefrontal control.

- Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT) remains a first-line, evidence-based treatment for depression and anxiety, but integration with existential techniques (e.g. addressing death anxiety, life values) enhances outcomes. Empirical studies find that existential concerns like fear of death and meaninglessness often underlie common disorders and can causally exacerbate symptoms.

- Psychodynamic models contribute an understanding of how early life experiences and relational patterns create enduring vulnerabilities (e.g. low self-worth, insecure attachment) that manifest in adult psychopathology. Modern neuropsychology validates some psychodynamic concepts (e.g. early trauma’s impact on the developing emotion regulation systems).

- Existential therapy principles (finding purpose, confronting freedom/responsibility, cultivating authenticity) have gained empirical support as protective factors. A 2023 meta-analysis of 99 studies (N=66,000+) found that a strong sense of life purpose correlates with significantly lower depression and anxiety (mean effect sizes r≈-0.5 for depression). This suggests that restoring meaning is not just philosophically but clinically important.

- Somatic and mind–body interventions (e.g. exercise, yoga, mindfulness meditation, biofeedback, somatic experiencing) show promising efficacy for chronic mental and somatic conditions. For instance, regular physical exercise produces moderate-to-large reductions in depressive symptoms, comparable to other treatments, and somatic therapies for trauma (like Somatic Experiencing) can alleviate PTSD and comorbid depression/anxiety.

Chronic Conditions Focus: Adults 25–50 with chronic conditions often present overlapping symptoms (e.g. an individual with depression may also have anxiety and IBS). An integrative approach allows simultaneous treatment of psychological distress and physical symptoms. For example, IBS is now defined as a gut–brain interaction disorder requiring combined medical and psychological care; gut-focused hypnosis or CBT significantly improves IBS symptoms by modulating both brain and bowel.

Case Vignette (Illustrative): A 45-year-old professional with persistent depression and IBS – She receives antidepressant medication (targeting neurochemistry) and CBT for negative thoughts. However, full recovery comes only after integrative therapy addresses deeper issues: exploring grief and self-identity conflicts (psychodynamic), rediscovering a sense of purpose beyond work (existential), and learning mind–body relaxation to calm her gut (somatic hypnosis). Her treatment team (psychiatrist, psychologist, nutritionist) collaboratively tailor this plan, leading to marked improvement in mood, bowel regularity, and overall life satisfaction. This case reflects real-world trends toward interdisciplinary care for complex cases.

Major Trends: Globally, mental health is recognized as a priority. One in eight people worldwide (970 million) had a mental disorder in 2019, with depression (~280 million) and anxiety (~301 million) most common. Rising comorbidity of mental and somatic illness has propelled integrated care models (e.g. primary care clinics embedding psychologists). There is growing acceptance of Eastern practices (mindfulness, yoga) in mainstream therapy, and emerging interest in psychedelic-assisted therapy to catalyze existential insight (an area of active research). Experts predict the next decade will see personalized integrative therapies become standard, leveraging neuroscience (e.g. brain imaging biomarkers) to inform psychological and lifestyle interventions tailored to the individual.

Evidence Base & Limitations: This report draws on peer-reviewed meta-analyses, longitudinal studies, and authoritative reviews (APA and WHO reports). Overall evidence supports each component of the integrated model, but research on combined approaches is still developing. Some integrative therapies (especially existential and somatic techniques) lack large-scale trials; their inclusion relies on theoretical rationale and smaller studies. Cited evidence is rated for strength: e.g. Level I (high) for CBT/exercise in depression (multiple RCTs, meta-analyses); Level II (moderate) for psychodynamic therapy (several RCTs/meta-analyses, though fewer than CBT); Level II for mindfulness-based therapies in anxiety/depression; Level III (preliminary) for existential and somatic therapies (promising results but limited RCTs). Integrating modalities raises methodological challenges (isolating which element drives improvement) and requires clinician training across paradigms. These limitations are discussed in depth, ensuring a critical perspective on what is known versus still speculative.

Actionable Insights: Clinicians are encouraged to adopt a bio-psycho-social-existential assessment lens – evaluating not just symptoms, but also a client’s brain health (e.g. sleep, substance use), cognitive patterns, relationships/attachment history, sense of meaning, and bodily stress symptoms. Treatment plans should be personalized: for some, antidepressants plus purpose-driven psychotherapy might be key; for others, trauma-focused bodywork plus cognitive coaching and meditation could be transformative. Individuals are advised that self-help should likewise integrate domains: for example, improving mood through regular exercise and mindfulness practice, and engaging in values-driven activities that enrich life meaning. Ethically, an integrative approach must respect client preferences and cultural values (e.g. incorporating spiritual beliefs if applicable). When well-implemented, this framework can not only alleviate symptoms but promote an “integrated self” – a state of authenticity, resilience, and aligned mind-body wellness that empowers long-term recovery.

Introduction

Mental health disorders are a leading cause of suffering and disability worldwide, and their impacts are widespread and long-lasting. As of 2019, approximately 13% of the global population (970 million people) lived with a diagnosable mental disorder. Depression and anxiety alone account for nearly half these cases, and rates have only risen – for instance, the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 precipitated a sharp 26–28% increase in depressive and anxiety disorders worldwide. Beyond diagnosable disorders, many adults grapple with chronic psychosomatic conditions like irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and traits or personality patterns (such as narcissism) that significantly impair well-being and relationships. Traditional approaches in psychiatry and psychology often silo these problems: one patient might see a psychiatrist for medication, a therapist for talk therapy, and a gastroenterologist for IBS – each addressing different “parts” of the person. This fragmented care risks missing the forest for the trees.

Holistic paradigm needed: Growing consensus suggests mental health must be approached holistically. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines mental health not merely as the absence of illness, but as a state of well-being in which an individual “realizes their abilities, copes with normal stresses, works productively, and contributes to community”. This definition inherently spans biological and existential dimensions – from coping with stress (a physiological and psychological process) to finding purpose in work and community (an existential and social construct). Moreover, WHO emphasizes that mental health arises from a “complex continuum” of influences. Individual biology (genetics, brain chemistry), life experiences, social context, and structural factors all intertwine to determine mental well-being. It follows that effective treatment and prevention must address this complexity: “multiple individual, social and structural determinants may combine to protect or undermine mental health”. In practical terms, this means integrated interventions are needed to reduce risks, strengthen resilience, and restore mental health on all these levels.

Integrating neuropsychology and existential psychology: This report explores an integrative framework that unites insights from clinical neuroscience (neuropsychology) and existential-humanistic psychology, alongside cognitive-behavioral and psychodynamic models and somatic therapies. We use “neuropsychological” to denote the broad neuroscientific understanding of mental processes – including brain structures, neural circuits, neuroendocrine and autonomic systems – as well as cognitive psychology foundations of behavior. By “existential,” we refer to the dimension of human experience concerned with meaning, values, purpose, freedom/responsibility, isolation/connection, and authenticity. These two realms – the biological and the existential – are often seen as disparate in both theory and practice. Indeed, throughout much of the 20th century, treatment philosophies diverged: one could choose a biologically oriented route (e.g. pharmacotherapy, ECT) or a psychological route (with camps like CBT focusing on observable cognition/behavior, and others like existential or psychodynamic therapy focusing on subjective experience and meaning). Each approach developed its own evidence base and successes, but also clear limitations when used in isolation.

- Example: Major Depressive Disorder has well-documented neurobiological correlates (such as hyperactivation of stress pathways and changes in brain structure in limbic regions and prefrontal cortex). Antidepressant medications that modulate neurotransmitters can reduce symptoms, validating the biological aspect. Yet depression is also characterized by feelings of hopelessness, loss of purpose, and distorted negative beliefs about oneself and the world – domains where psychotherapy, especially meaning-oriented therapy, can be transformative. If treatment only addresses the biology (e.g. medication) but not the person’s life narrative and sense of self, residual symptoms or relapses are common. Conversely, therapy alone without relief from severe neurovegetative symptoms (sleep, energy, appetite dysregulation rooted in brain–body imbalance) may not fully succeed. This calls for blending approaches.

Increasingly, researchers and clinicians are working to bridge these gaps. Since 2000, there has been a surge in interdisciplinary studies: neuroscientists study mindfulness meditation’s effects on the brain, cognitive therapists incorporate principles of acceptance and values (from existential and Eastern traditions), psychodynamic therapists draw on attachment neuroscience, and medical experts recognize the role of stress and meaning in physical illnesses like IBS. Notably, “existential issues are increasingly discussed in empirical clinical psychology”. For example, fear of death – long a focus of existential philosophy – has been empirically linked to anxiety disorders; experimental work even suggests death anxiety can causally amplify psychopathology. Such findings underscore that existential distress has measurable mental health impacts, and addressing it can enhance outcomes. At the same time, advanced brain imaging shows that psychological therapies can induce quantifiable neural changes, reinforcing that talk therapy can be a biological intervention as well.

Report scope and objectives: This comprehensive report aims to:

- Synthesize global research (2000–2025) on integrated models of mental health, highlighting especially the past ~15 years of findings that connect neurobiology, cognitive-behavioral science, psychodynamic concepts, and existential theory. Primary sources include peer-reviewed journals (meta-analyses, clinical trials, neuroscience studies) and authoritative reports (e.g. APA guidelines, WHO 2022 World Mental Health Report). Eastern philosophical perspectives (e.g. Buddhism, Taoism) are included to enrich the conceptual framework where relevant, as these traditions offer millennia-old insights into mind-body integration and the pursuit of meaning.

- Apply the framework to specific conditions: depression, anxiety, addiction, IBS, and narcissism. These were chosen as they represent a mix of internalizing disorders, behavioral disorders, psychosomatic illness, and personality pathology – illustrating the versatility of an integrative approach. Each condition’s section will examine how various factors (brain, psyche, relationships, and existential issues) converge in that disorder, and how treatment modalities can be combined for synergy.

- Identify key trends, case studies, and stakeholders: The report will note major players in research or clinical innovation (for instance, Viktor Frankl’s logotherapy in existential therapy; Aaron Beck in CBT; emerging figures in “neuropsychoanalysis” and mind-body medicine). We also discuss opposing viewpoints – e.g. critiques that integrative approaches might be too “wooly” or that existential therapy lacks empirical rigor – to provide a balanced analysis. Ethical considerations, such as cultural sensitivity and avoiding reductionism, are addressed to ensure the framework is applied responsibly.

- Provide actionable insights and future directions: In conclusion, the report will offer recommendations for clinicians (how to start integrating these principles in practice), for patients (self-help strategies that align with the integrated model), and for the mental health field (research gaps to fill, predicted developments such as integrative training curricula).

Neutral tone and structure: In line with a formal analytical report, the following sections are organized by thematic headings. We begin with foundational perspectives (neuroscientific, cognitive-behavioral, etc.) to establish the components of the framework. We then delve into each condition as a “case study” in integration. Visual figures are included in an Appendix to illustrate key concepts (e.g. a diagram of brain regions involved in emotion, and a gut–brain axis schematic). Citations are provided in APA style (author-year context in text, with source links in brackets) to substantiate all factual claims. The evidence strength is noted where applicable (e.g. whether a statement comes from a large meta-analysis vs. a single study). By weaving together diverse strands of knowledge, this report endeavors to demonstrate that an integrated neuropsychological-existential approach is not only theoretically sound but practically necessary for addressing the full reality of mental suffering – and ultimately, for helping individuals achieve not just symptom reduction, but a more authentic and meaningful life in recovery.

Theoretical Foundations of an Integrated Approach

Effective integration requires understanding what each contributing framework offers. Here we outline five key perspectives – clinical neuroscience, cognitive-behavioral, psychodynamic, existential, and somatic (mind-body) – and summarize their core concepts, contributions to explaining mental disorders, and empirical support. We then briefly include insights from Eastern philosophies that complement these Western models. Throughout, we highlight how these perspectives intersect and inform each other, laying the groundwork for a unified model.

Clinical Neuroscience Perspective

Modern clinical neuroscience provides an unparalleled window into the biological substrates of mental health. Techniques like functional neuroimaging, neuroendocrine assays, and neuropsychological testing have mapped out how certain brain circuits and physiological processes correlate with mood, cognition, and behavior. Key principles from this perspective include:

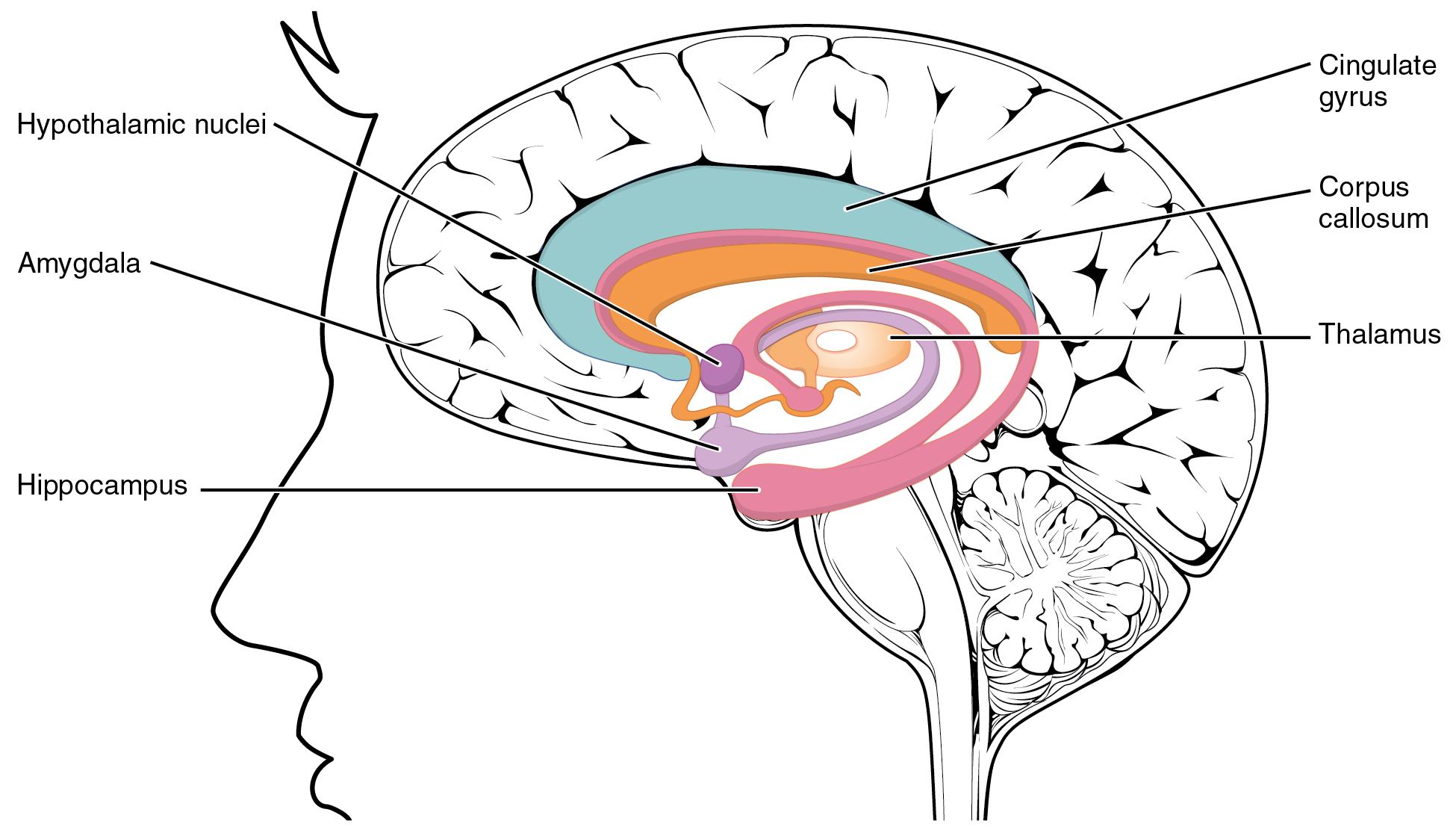

Brain Circuitry and Neurotransmitters: Many mental conditions are linked to dysregulation in specific neural networks. For example, depression has been associated with hyperactivity of the “default mode network” (leading to ruminative self-focus) and hypoactivity in reward circuitry (striatum). Core limbic structures – the amygdala (processing fear and emotion), hippocampus (memory and mood regulation), and parts of the prefrontal cortex (executive control, emotion regulation) – show functional and structural changes in depression. (Figure 1 in the Appendix illustrates some of these brain regions.) Anxiety disorders similarly involve an overactive amygdala and underactive prefrontal inhibitory control, producing exaggerated fear responses to threats. Addiction hijacks the brain’s reward pathways (midbrain dopamine circuits) and weakens frontal inhibitory control, rendering the individual less able to resist cravings. These insights have largely come from neuroimaging and neurochemical studies. They explain, for instance, why antidepressant medications (which increase neurotransmitters like serotonin and norepinephrine) can help rebalance mood, or why benzodiazepines (which enhance GABA, an inhibitory neurotransmitter) can dampen acute anxiety by calming overactive neural firing. Neuroscience thus grounds the biological component of mental illness, treating the brain as an organ that can malfunction – much like the heart in cardiovascular disease.

Chronic Stress and the HPA Axis: A unifying neurobiological theme across many disorders is the role of chronic stress and the Hypothalamic–Pituitary–Adrenal (HPA) axis. The HPA axis is the body’s central stress response system, releasing cortisol and other stress hormones during threat or adversity. In healthy situations, the HPA axis activation is acute and self-limited. But chronic psychosocial stress can lead to HPA axis overdrive or dysregulation, which has downstream effects: elevated cortisol can damage neurons (especially in the hippocampus), promote inflammation, and disrupt neurotransmitter systems. Depression is often characterized by HPA hyperactivity – many depressed patients have elevated cortisol levels or blunted diurnal cortisol variation. This has led to the hypothesis that some depression is a state of “stress injury” to the brain. Indeed, neuroimaging has shown that individuals with long-term depression may have a smaller hippocampus volume on average (thought to result from chronic stress neurotoxicity or reduced neurogenesis). The inflammatory response is related: chronic stress can trigger pro-inflammatory cytokines, and elevated inflammation markers are found in a subset of depressed patients (sometimes called “inflammatory depression”). These findings open doors to novel treatments – e.g. anti-inflammatory medications or stress-reduction techniques – and underscore that psychological stressors have physical embodiments in the brain and body.

Neuroplasticity and Psychotherapy: Crucially, neuroscience is not only about medication or biological interventions; it also validates psychotherapy by revealing neuroplastic changes associated with psychological treatment. Studies using fMRI and PET scans have observed that after a course of successful therapy, patients’ brain function can change in specific ways. For example, after CBT for anxiety, patients often show reduced hyperactivity in the amygdala and increased activity in frontal regions when confronting feared stimuli. One systematic review found that across anxiety disorders, “successful psychotherapy is linked to functional neural changes in prefrontal control areas and fear-related limbic regions” – essentially, therapy strengthens the brain’s executive control over emotion, much like medication does. In depression, psychotherapy (CBT or interpersonal therapy) has been associated with normalization of overactive limbic areas and increased prefrontal cortex metabolism in some studies. A meta-analysis comparing psychotherapy and antidepressants found both produce overlapping brain changes, though via partly different pathways. These findings debunk the false dichotomy “therapy vs. biology” – therapy works through biology, by harnessing learning and plasticity. A notable example: Mindfulness meditation training (often from Buddhist tradition, but now integrated into mental healthcare) has been shown to alter brain structure (e.g. increasing gray matter density in areas related to attention and emotion regulation) and function (reducing activation of stress regions) in those who practice regularly.

Genetics and Individual Differences: Another contribution of neuroscience is illuminating why certain individuals develop mental illness under stress while others do not. Genetic factors (heritability) account for a portion of risk in disorders like depression, anxiety, and substance dependence. Additionally, gene–environment interactions have been identified (e.g. certain gene variants in serotonin transport may make one more vulnerable to depression if traumatic events occur). These insights encourage personalized approaches – for instance, someone with a strong family history of depression might benefit from earlier preventive interventions (lifestyle changes, therapy) during high stress. It also reminds clinicians to destigmatize mental illness by explaining its partial biological basis; patients often feel relief hearing that “depression is an illness with neurochemical aspects,” not a personal weakness. However, a balanced view is needed: simplistic notions like the “chemical imbalance” theory of depression (often interpreted as serotonin deficit) are now considered an oversimplification. Recent reviews find that depression cannot be reduced to any single neurotransmitter deficiency – it’s far more complex. Thus, neuroscience supports a multi-factorial model rather than a reductionist one.

In summary, the clinical neuroscience perspective contributes a rigorous understanding of the brain and body in mental health. It provides targets for pharmacological and neuromodulatory treatments and evidence that psychosocial interventions have biological effects. Its strengths include a strong empirical base (many findings replicated, biological measures quantifiable) – Level I evidence for many claims (e.g. numerous RCTs show medications outperform placebo in acute depression; meta-analyses show exercise has effect size ~0.6 for depression). Limitations of a purely neuroscientific approach are that it may neglect the subjective meaning of symptoms, the patient’s narrative, and environmental context. Medications can alleviate symptoms but often do not address why a person became ill or how to build a fulfilling life. Moreover, not all patients respond to drugs, and some conditions (like personality disorders) have no specific pharmacologic cure. This necessitates integrating neuroscience with psychological and existential care – using the biological insights in service of a more comprehensive healing process.

Figure 1 (Appendix): Key Brain Regions Implicated in Emotion and Memory. The limbic system, including the amygdala (turquoise) and hippocampus (pink), works with cortical areas like the cingulate gyrus (green) and prefrontal regions to regulate mood and anxiety. Chronic stress and depression can cause functional changes in these areas, highlighting the need to address both brain and mind in treatment.

Image source: Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0

Cognitive-Behavioral Model

The cognitive-behavioral model (encompassing Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy and its variants) offers a structured, present-focused approach to mental health disorders. At its core is the idea that maladaptive thought patterns and behaviors maintain psychological distress, and that by changing how one thinks and behaves, one can relieve symptoms. Key tenets include:

Cognitive distortions and schemas: Aaron Beck’s cognitive theory of depression posits that depressed individuals develop negative schemas about themselves, the world, and the future (the “cognitive triad”). These schemas often stem from early experiences and fuel distorted thinking. Examples of common distortions are overgeneralization (“I failed at this job, so I’ll fail at everything”), catastrophizing (“If I have a panic attack, I’ll go crazy or die”), and all-or-nothing thinking (“If I’m not perfect, I’m worthless”). In anxiety disorders, there is often an overestimation of threat and underestimation of coping ability. Cognitive therapy helps patients identify these distortions, challenge their accuracy with evidence, and reframe thoughts into more balanced, realistic ones. For instance, a person with social anxiety might learn to catch the thought “Everyone will judge me if I blunder” and replace it with “People are probably focused on themselves; even if I make a mistake, it’s okay.” Over time, this cognitive restructuring can reduce anxiety. The empirical support here is robust: dozens of RCTs have shown that modifying dysfunctional thoughts via CBT significantly reduces anxiety and depressive symptoms (Level I evidence). Furthermore, research in neurocognitive science shows that such cognitive changes can be observed as changes in attention and memory biases (e.g. after CBT, formerly depressed patients pay less automatic attention to negative stimuli) – which ties back to neural changes as well.

Behavioral conditioning and avoidance: Behavioral theory (from Pavlov, Skinner, etc.) contributes the understanding that much of psychopathology is reinforced by maladaptive behaviors. For example, in addiction, the substance use behavior is reinforced by immediate rewards (pleasure, relief) despite long-term costs. In phobias or PTSD, avoidance behaviors (avoiding driving after an accident, for instance) provide short-term anxiety relief, but prevent the individual from disconfirming their catastrophic predictions, thus maintaining the fear. Behavioral interventions aim to break these cycles. Exposure therapy is a prime example: by gradually and repeatedly confronting feared stimuli or memories in a safe manner, the person learns new associations (“this is not actually dangerous”) and the conditioned fear response extinguishes over time. Similarly, behavioral activation for depression works by increasing engagement in meaningful or rewarding activities despite low motivation; this can jump-start positive reinforcement and improve mood. These techniques are strongly evidence-based – exposure is a gold-standard treatment for phobias, panic disorder, and OCD, with high success rates (often 60–80% of patients significantly improve) and long-term efficacy. Behavioral activation has been shown to be as effective as full cognitive therapy for many cases of depression, highlighting that sometimes changing behavior (even before thoughts) can directly improve brain function and mood (through increased rewarding experiences and sense of mastery).

Skills training and coping strategies: CBT also involves teaching practical skills, such as problem-solving techniques (for handling stressful situations systematically), relaxation and breathing exercises (to counter physiological arousal in anxiety), and social skills or communication training (for those with social anxiety or interpersonal problems). In addiction treatment, CBT includes identifying triggers, avoiding high-risk cues, and developing alternative coping (e.g. urge surfing, distraction techniques). These skills empower patients to manage their symptoms in real-world situations. A meta-analytic review of CBT across disorders found that acquiring these coping skills mediates therapeutic outcomes – patients who internalize CBT skills tend to have lower relapse rates because they effectively become “their own therapists” after treatment.

Thoughts, feelings, behaviors triangle: CBT conceptualizes a feedback loop: thoughts influence feelings, feelings influence behaviors, and behaviors influence thoughts. For example, a person feels depressed (feeling), so they withdraw and stay in bed (behavior), which then leads to more negative self-thoughts (“I’m useless, I can’t even get up”), which worsens the depression – a vicious cycle. By intervening at the level of thoughts (cognitive therapy) or behaviors (behavioral activation), CBT breaks the cycle. This clear model helps patients understand their condition not as a mysterious force but as a set of patterns they can learn to shift. It demystifies mental illness and encourages a problem-solving attitude.

One reason CBT is crucial in an integrative framework is its strong evidence base and adaptability. Since the 2000s, CBT has been manualized for countless conditions (including adaptations like Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT) for borderline personality disorder and Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) – a “third-wave” CBT that introduces mindfulness and values, bridging into existential territory). Meta-analyses consistently show CBT’s effectiveness: for moderate depression, effect sizes ~0.7 vs control; for panic disorder, up to 80% panic-free rates; for insomnia, CBT-I is as effective as medications. Moreover, CBT outcomes are often durable, especially when booster sessions or continuation are provided, because of the skills learned. This is not to say CBT is infallible – a significant minority of patients do not respond, and some disorders (e.g. complex trauma or entrenched personality disorders) may need more than structured CBT can offer. Critics have also noted that CBT alone may ignore deeper existential or relational issues, focusing on symptom alleviation without addressing underlying “root causes” like lack of meaning or unresolved grief. In fact, cognitive therapists historically downplayed topics like death anxiety or spiritual despair, seeing them as outside the therapy’s scope. However, this attitude has been changing. Recent literature in CBT acknowledges the importance of existential themes: therapists are encouraged, for instance, to discuss a patient’s values and life purpose as part of treatment planning. Values work is central in ACT, and even traditional CBT for depression now sometimes incorporates identifying personal goals and sources of meaning (countering the depressive hopelessness). As one paper noted, “existential concerns are common themes in CBT” and training programs have begun to include them. This evolution of CBT indicates it is a flexible, integratable modality.

In an integrative approach, CBT techniques can be the “grounding” or symptom-focused component that ensures tangible change occurs (e.g. the person actually starts sleeping better, leaves the house more, has fewer panic attacks). At the same time, other components (psychodynamic or existential) can enrich CBT by addressing domains CBT might miss (like childhood roots of a schema, or the patient’s search for identity). Thus, cognitive-behavioral methods are usually part of any comprehensive treatment plan – they are the workhorse interventions that can be blended with others. The strength of evidence (Level I) and clarity of CBT make it a reliable foundation. Its limitation – a tendency to be manualized or scripted – can be mitigated by a skilled therapist who tailors the approach and brings in existential depth where appropriate (for example, using a cognitive approach to challenge a client’s belief “My life has no meaning” and helping them construct a new narrative that does include meaning, thus merging cognitive restructuring with existential exploration).

Psychodynamic and Attachment Theory Perspective

Psychodynamic psychology, originating from Freudian psychoanalysis and later schools (Jungian, object relations, self psychology, attachment theory), contributes a developmental and depth-oriented perspective on mental health. While classical psychoanalysis is less common today in pure form, psychodynamic concepts heavily influence integrative therapy, especially for chronic personality-related issues (like narcissism) and complex trauma. Key contributions include:

Unconscious processes and defense mechanisms: Psychodynamic theory proposes that much of our mental life is unconscious – feelings or memories deemed too threatening or painful are pushed out of awareness (repressed), yet still affect us. For example, a person who grew up with a highly critical parent might unconsciously harbor intense shame and anger; as an adult, they may develop depression (turning the anger inward) or overachieve to cope with feelings of inadequacy. Therapists working dynamically pay attention to slips of the tongue, recurring themes, fantasies, or seemingly irrational symptoms as clues to these hidden emotional truths. Defense mechanisms are central here – the mind’s tactics to avoid distressing truths. Common defenses include denial (refusing to accept reality), projection (attributing one’s unacceptable feelings to others), and rationalization (finding logical excuses for emotional behavior). In narcissistic personality, for instance, one sees defense mechanisms like grandiosity (inflated self-importance to ward off deep-seated shame) and splitting (viewing people as all-good or all-bad to avoid complex ambivalent feelings). Recognizing and gently confronting maladaptive defenses can help patients face and process what they’ve avoided (e.g. a deep fear of being unlovable), leading to more authentic and adaptive functioning. Modern therapy often integrates this with CBT by helping clients notice when a defense (say, intellectualizing feelings) might be hindering emotional engagement in treatment.

Attachment and relational patterns: Psychodynamic and attachment theories emphasize the formative impact of early relationships on personality and mental health. John Bowlby’s attachment research (mid-20th century) showed that children’s early bonding experiences with caregivers shape their expectations in later relationships and their ability to regulate emotions. If early attachments were secure (caregiver was consistently responsive), the individual tends to develop a stable self-esteem and resilience. If attachments were insecure (caregiver was neglectful, or inconsistent, or abusive), the individual may develop core schemas like “I cannot rely on others” or “I am not worthy of love,” which contribute to anxiety, depression, or personality disorders. For example, many addiction cases have roots in early emotional deprivation – the substance may symbolically serve as a comforting figure or a way to numb the emptiness from lack of secure attachment. Psychodynamic therapy often involves examining the client’s relationship patterns, including how they relate to the therapist (the therapeutic alliance). The concept of transference – where feelings from past relationships are unconsciously transferred onto the therapist – is a tool to understand the client’s internal world. If a client finds themselves, say, irrationally worried that the therapist will judge or abandon them after a minor issue, this could reflect a childhood pattern of a critical or abandoning parent. By working through this in therapy (therapist remains consistent and empathic, and they discuss these feelings openly), the client can “re-wire” their attachment expectation, experiencing a new kind of relationship. This, in turn, can generalize to outside relationships. Empirical support: Attachment-focused interventions have shown efficacy, especially in treating interpersonal problems and some personality disorders. Studies of Transference-Focused Psychotherapy (TFP) or Mentalization-Based Treatment (MBT) for borderline personality disorder (BPD) – both psychodynamic approaches targeting attachment and identity – have found significant reductions in self-harm and improved functioning (Level II evidence, as the trials are fewer than for CBT but outcomes are promising). Neurobiologically, research by Allan Schore and others on affect regulation suggests early attachment trauma can lead to right-brain developmental deficits, impairing emotional regulation capacity; thus therapy that provides a corrective emotional relationship can potentially foster new neural integration in emotion-regulating circuits.

Meaning of symptoms and the “integrated self”: Psychodynamic therapists often ask why a symptom exists in a particular psychological context, viewing symptoms as potentially meaningful (or at least linked to underlying conflicts). For example, irritable bowel flares might coincide with periods when the person is “stomaching” great stress or anger unexpressed – a psychodynamic view of psychosomatic IBS might explore if the bowel symptoms are an embodiment of emotional turmoil that has no other outlet. Similarly, from a classic Freudian perspective, an addiction might be understood as a substitution for unmet needs (sometimes called “self-medication” of anxiety or depression). One salient concept is the development of an integrated self. Healthy personality development involves integrating various parts of the self (e.g. one’s loving side and angry side, one’s ideal self and real self, etc.) into a coherent whole. If integration fails, mental disturbance can manifest. Narcissistic personality disorder, for instance, has been described by Heinz Kohut as arising from a fragmented self that never cohesively formed because of childhood empathic failures – leading to alternating feelings of grandiosity and worthlessness. Therapy aims to help such individuals develop a more stable, realistic self-image by processing early wounds and building capacity for self-soothing and empathy. Recent neuropsychological models (e.g. by Julius Kuhl, 2015) even attempt to ground the “integrated self” in brain terms – suggesting that certain right-hemisphere networks might enable integrating emotion, memory, and self-representations. The integrated self is thought to have functions like “emotional connectedness, broad vigilance, utilization of felt feedback, unconscious processing,” etc., which contribute to authenticity and coherence. Though these models are theoretical, they illustrate an important point: identity and self-structure are vital targets in therapy, especially for chronic conditions where a person’s identity may be entangled with illness (“I am a depressed person”) or defense (“I must be perfect or I’m nothing”).

Psychodynamic therapy today: In practice, psychodynamic therapy has evolved from the old image of a silent analyst and years on a couch. Modern short-term psychodynamic therapy (STPP) is often time-limited (12–20 sessions) and focuses on a central issue. Meta-analyses (e.g. Abbass et al., 2014) have found STPP can significantly improve depression and anxiety, with effect sizes in the moderate range, and importantly, these gains often strengthen over time after therapy ends – a phenomenon attributed to patients internalizing the ability to reflect on themselves (so-called “sleeper effects”). This suggests psychodynamic work might instigate deeper shifts that continue as the patient’s self-insight grows. Another important piece is trauma processing: approaches like Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) or somatic trauma therapy (related to psychodynamic in addressing implicit memory) acknowledge that traumatic memories are often stored non-verbally and need specialized techniques to integrate into the narrative self (preventing flashbacks, etc.).

In an integrative framework, the psychodynamic perspective ensures that therapy is not merely symptom-focused but also person-focused – it attends to the personal history, the unique meanings a symptom might hold, and the therapeutic relationship itself as a vehicle for change. It is particularly useful for chronic, recurrent cases that haven’t responded to brief manualized therapy, hinting at deeper issues (like a patient who is intellectually adept at CBT techniques but still feels empty and relapses – this might indicate unresolved inner conflicts or lack of self-worth that require a different approach). By integrating psychodynamics, clinicians can help patients achieve not just symptom remission but also personal growth: resolving old wounds, improving relationship patterns, and developing a more integrated self capable of sustaining wellness. The challenge is that psychodynamic work can be longer-term and harder to quantify; thus combining it with structured methods (CBT, skills training) can offer the best of both – quick relief and deep change. When appropriate, referrals or concurrent involvement of different therapists (one for medication/CBT, another for deeper therapy) might be used, but often a single clinician can flexibly move between supportive cognitive work and insight-oriented exploration as needed.

Existential Psychology Perspective

Existential psychology addresses the ultimate concerns of human existence – issues of meaning, purpose, freedom, isolation, and mortality – and how confronting (or avoiding) these issues can shape mental health. This approach is rooted in the philosophies of thinkers like Søren Kierkegaard, Friedrich Nietzsche, Martin Heidegger, and Jean-Paul Sartre, and was brought into therapy by figures such as Viktor Frankl, Rollo May, and Irvin Yalom. While classical existential therapy is non-directive and philosophical, its concepts have seeped into many contemporary interventions. Key themes and their relevance are:

Meaning and purpose (Will to Meaning): Viktor Frankl, a Holocaust survivor and psychiatrist, famously observed that humans have a fundamental “will to meaning,” and when this drive is frustrated or unfulfilled, psychological problems arise. He termed the pervasive sense of emptiness the “existential vacuum,” which can manifest as boredom, apathy, or nihilism. Frankl noted correlations between meaninglessness and depression, addiction, and aggression in society. Indeed, absence of meaning has been implicated in substance abuse (people seeking relief or a sense of aliveness) and even in suicidal ideation (when one concludes life has no purpose). Conversely, having a purpose in life is protective: as cited earlier, a large meta-analysis in 2023 confirmed that greater purpose in life is associated with significantly lower depression and anxiety across diverse populations. The effect size was quite large (r ≈ -0.5 for depression), rivaling or exceeding many medical or psychological risk factors in impact. This suggests that fostering a sense of meaning can be a powerful therapeutic lever. Existential therapy (and related approaches like logotherapy) explicitly helps clients discover meaning in their suffering and life experiences. In practice, this might involve exploring values, identifying meaningful goals, or reframing a hardship as an opportunity for personal growth or contribution. For example, a client with depression might find meaning through creative expression or helping others with similar struggles, transforming a feeling of uselessness into a sense of purpose. Even when life circumstances cannot be changed (as in terminal illness or irreversible loss), finding meaning in how one endures can alleviate despair – a concept Frankl illustrated with Holocaust survivors. From a treatment standpoint, meaning-centered interventions have empirical support in specific contexts: e.g. Meaning-Centered Therapy for cancer patients has shown efficacy in reducing despair and enhancing spiritual well-being in randomized trials (Level II evidence). In non-terminal populations, techniques from positive psychology, such as identifying “signature strengths” and using them in service of something larger, have improved depressive symptoms in some studies.

Freedom, responsibility, and authenticity: Existentialists emphasize that with freedom of choice comes the burden of responsibility for one’s life. Many people experience existential anxiety when confronting the vast freedom they have (or the feeling of lack of structure) – this can lead to indecisiveness or avoidance of choices. Alternatively, people may deny their freedom by adopting rigid societal roles or others’ expectations, leading to an inauthentic life. Authenticity in this context means living in accordance with one’s true self and values, rather than in “bad faith” (pretending one has no choice or following an imposed identity). An authenticity deficit can cause or exacerbate mental distress; for instance, someone who pursued a career path to please their parents but finds no joy in it may feel empty or anxious without understanding why. Research in psychology has linked authenticity to well-being – studies show that authentic individuals have better psychological health and a greater sense of meaning in life. One study found perceived authenticity correlates with higher self-esteem and life satisfaction. However, authenticity is complex: a 2024 study indicated that authenticity’s apparent mental health benefits might be accounted for by self-esteem and executive functioning – implying that being authentic often coincides with having good self-worth and self-regulation, which are the true drivers of well-being. Regardless, therapy often involves helping people peel away social masks and connect with their genuine feelings and desires. Techniques include examining times when a client feels they are “wearing a mask” or betraying their own values, and encouraging experiments in more authentic living (e.g. asserting one’s true opinion, pursuing a passion). The integrated self concept intersects here: achieving authenticity requires integrating disowned parts of self (perhaps a client hides their artistic side because it was mocked in youth; reclaiming it could be key to their vitality). Existential therapy holds the client accountable to take responsibility for their choices – moving from a victim stance (“I have to do X”) to an ownership stance (“I choose to do X or not, and accept the consequences”). This can be very empowering, though also challenging if a person has been avoiding responsibility. It must be balanced with compassion and understanding of real constraints (not to blame the victim of circumstances but to maximize agency where possible).

Existential anxiety and confronting death: All humans grapple with the fact of their mortality and the uncertainty of life’s meaning. Death anxiety – even if unconscious – can underlie various psychopathologies. For example, terror management theory in psychology suggests that reminders of mortality can make people cling harder to defenses (like material success, or rigid beliefs) as a way to feel immortal symbolically. In clinical practice, fear of death or illness can manifest as health anxiety, panic attacks (which often include fear of dying during panic), or obsessive-compulsive behaviors aimed at controlling risk. Irvin Yalom described four ultimate concerns (death, freedom, isolation, meaninglessness) that therapy should help clients face rather than flee. When these fears are unacknowledged, they may surface in disguised forms. There is some experimental evidence: one study found that addressing death anxiety directly in therapy (with exposure and reflection techniques) helped reduce a variety of anxiety symptoms. Another found that high death anxiety predicted worse mental health across diagnoses, and reducing it improved outcomes. Thus, an integrative therapist might gently probe if, say, a 38-year-old client’s recent depression could partly stem from a mid-life awareness of mortality or aging. By bringing this into the open, the client can work on accepting mortality and focusing on what makes life valuable despite its finite nature – a process that can alleviate depressive hopelessness. Existential therapies do not shy away from spiritual or philosophical discussions: if a client is religious, exploring how their faith helps with existential anxieties (or is contributing to them) is welcome; if a client is secular, discussing their worldview, legacy, or how they create meaning in a potentially random universe is equally important. In many cases, self-transcendence is a healing response to death anxiety – that is, shifting focus from oneself to something larger (family, community, cause, creativity) provides solace and purpose. As one paper put it, self-transcendence can be seen as “non-dual organismic interconnectedness with everything that is” – an experience often described in spiritual terms (feeling at one with life) that powerfully counters existential isolation and fear. Notably, this is where Eastern philosophies align: Buddhism teaches acceptance of impermanence and the no-self concept, which, when truly internalized, can paradoxically reduce fear of death (if there is no fixed self, death is just a transformation). We will return to Eastern perspectives shortly.

Therapeutic stance and techniques: Existential therapy tends to be less technique-driven and more dialogical. The therapist often works as a fellow traveler – openly engaging the client about life’s challenges, sometimes sharing their own reflections (in a measured way) to model honesty and courage. The relationship is one of true encounter; as Carl Rogers also noted (Rogers’ humanistic approach overlaps existential), a genuine, empathic therapeutic relationship itself is healing. Specific interventions might include guided imagery (imagine you are at the end of your life – what would you regret? what would you be proud of?), which can clarify values and priorities. Another is helping clients make meaning of pivotal life events (the “ABC” approach in meaning-making: identify an Adversity, find the Beliefs or interpretations about it, and examine the Consequences for meaning – somewhat akin to cognitive ABC but focused on existential beliefs). Logotherapy exercises involve techniques like paradoxical intention (humorously exaggerating a feared outcome to defuse it) and dereflection (shifting attention away from obsessive problems toward meaningful pursuits). Case studies abound of people overcoming immense adversity by finding meaning – for example, survivors of trauma who channel their experience into advocacy or helping others often achieve post-traumatic growth rather than PTSD.

Empirical research on pure existential therapy per se is limited (there are fewer RCTs because it’s hard to manualize existential conversations). However, as noted in the Heidenreich et al. (2021) review, “existential concerns…are frequently encountered by CBT therapists”, and integrating them doesn’t detract from outcomes. In fact, therapies explicitly targeting meaning (like Meaning-Centered Group Therapy for older adults or Existential CBT adaptations) have shown positive effects on depression and anxiety compared to controls. Given the meta-analytic data on purpose in life mentioned earlier, one could argue that any therapy ignoring existential wellbeing is overlooking a major determinant of mental health. Thus, an integrative approach incorporates existential assessment: e.g., asking “What gives you a sense of meaning or purpose?”; “How do you view the difficulties you are facing in terms of your life story?”; “What do you most regret, and what would you like your future to stand for?” Answers to these questions can guide interventions (if someone realizes their job feels meaningless, part of therapy might involve career or life changes that align better with their values, alongside treating symptoms).

In sum, the existential perspective adds depth and humanism to the framework. It ensures that treatment is not just about symptom removal but also about helping the person live a life that feels worth living. It reminds us that a person can have all the “right” external conditions (good job, medication controlling symptoms, supportive family) and still suffer internally from a crisis of meaning or identity. Addressing that directly can be the missing piece that allows full recovery. Ethically, existential work respects the client’s autonomy – rather than the therapist being the “expert” with answers, the client is guided to find their own answers to existential questions, which is empowering. This approach, of course, should be tailored to the client’s readiness; some may be overwhelmed by too much existential talk early on, so timing and blending with other methods is key.

Somatic and Mind-Body Therapies Perspective

The somatic perspective recognizes the unity of mind and body in mental health. It posits that psychological distress is often accompanied by bodily manifestations – and conversely, working with the body can affect the mind. Somatic therapies encompass a range of practices: some are more “medical” (like using physical exercise or nutrition as treatment), while others are specific psychotherapeutic approaches that involve bodily awareness and movement (like Somatic Experiencing, sensorimotor psychotherapy, or breathwork). Key points include:

The body keeps the score (trauma in the body): A now-famous phrase by Dr. Bessel van der Kolk captures how traumatic experiences, especially, are often encoded in bodily sensations and implicit memory rather than verbal narrative. People with PTSD may have somatic symptoms like chronic tension, dizziness, or pain with no medical cause, which relate to the physiological imprint of trauma (dysregulated autonomic nervous system, increased inflammation, etc.). The Polyvagal Theory (Stephen Porges) provides a framework: it suggests our vagus nerve mediates states of safety vs. danger; in trauma, people may get locked in fight/flight (sympathetic overdrive) or freeze (dorsal vagal shutdown) modes. Somatic therapies help clients regulate their nervous system by working directly with breath, posture, and movement to restore a sense of safety and connection. For example, Somatic Experiencing (SE) guides individuals to slowly release trauma-based tension by completing the bodily “fight or flight” actions that were thwarted during the original trauma (in a safe environment). A scoping review in 2021 found initial but promising evidence that SE effectively reduces PTSD symptoms and also has positive effects on depression, anxiety, and physical complaints. However, it noted the need for more rigorous studies (some existing ones lacked control groups). Nonetheless, in practice many trauma clinics now integrate body-focused techniques because purely cognitive talk therapy sometimes cannot access deeply stored traumatic memories. For chronic conditions like complex PTSD or somatic symptom disorders, adding a somatic component often improves outcomes (Level III evidence trending toward II as research grows).

Psychophysiology of IBS and pain: IBS is a prime example of a disorder at the mind-body interface. It involves real physiological dysregulation of gut motility and sensitivity, but is strongly modulated by stress and emotions. Patients often notice symptom flares during periods of anxiety or suppressed anger. The Gut–Brain Axis (illustrated in Figure 2, Appendix) is the bidirectional communication network between the central nervous system and the gastrointestinal system, involving neural pathways (vagus nerve), hormonal pathways (cortisol, gut hormones), and immunological pathways (cytokines). Psychological stress can alter gut microbiota and intestinal inflammation, contributing to IBS symptoms. Conversely, gut issues can send signals to the brain that affect mood (ever felt irritable due to indigestion? – that’s gut-brain signaling). Recognizing this, treatments for IBS increasingly use brain-gut therapies. Two standout interventions are gut-directed hypnotherapy and CBT for IBS, which have strong evidence. For instance, multiple randomized trials and meta-analyses show that hypnosis focused on soothing the gut can significantly reduce IBS pain, bloating, and bowel dysfunction, with effects lasting months or years. One review noted “cognitive-behavioral interventions and gut-directed hypnosis have the largest evidence for short-term and long-term efficacy in IBS”, leading European and North American gastroenterology guidelines to recommend them as second-line treatments. The American College of Gastroenterology’s 2021 guidelines even include psychological therapy (CBT or hypnotherapy) as part of standard IBS management. This is a landmark acknowledgment of mind-body integration in a traditionally medical field. Patients who engage in these therapies often learn how to calm their gut via relaxation techniques, visualization, and changing catastrophic thoughts about symptoms (“this pain means I might have cancer” is reframed to “this pain, while uncomfortable, is benign and will pass”). The result can be improvements comparable to dietary changes like the low-FODMAP diet. So, for somatic conditions with psychiatric overlays (IBS, fibromyalgia, chronic pain), integrating psychotherapy yields tangible physical relief.

Physiological regulation techniques: Many somatic-focused techniques aim at down-regulating chronic hyperarousal or correcting under-arousal. Breathing exercises are fundamental – teaching diaphragmatic breathing can activate the parasympathetic “rest and digest” response, reducing anxiety and even symptoms like heart palpitations. Progressive muscle relaxation (PMR) and biofeedback help patients recognize tension and consciously release it, which can break the vicious cycle of muscle tension causing pain causing more anxiety. Yoga combines breath control, meditation, and physical postures; numerous studies show yoga can reduce anxiety and depressive symptoms (often as an adjunct) and improve stress hormone profiles. A 2017 meta-analysis found yoga had a significant positive effect on anxiety (effect size ~0.65) and on depression (~0.55) compared to no treatment, although in rigorous comparisons it may be on par with other active interventions. Yoga’s advantage is it engages both mind and body and has broader wellness benefits (flexibility, cardiac health). Tai Chi and Qigong (from Chinese tradition) similarly have shown benefits for mood, likely through gentle movement, breath, and focus. These practices embody Eastern principles of balancing energy (“qi”) and could be seen as somatic-existential – as they often incorporate philosophical elements about harmony and grounding in the present.

Exercise as medicine: Physical exercise is a powerful (and underutilized) somatic intervention for mental health. As mentioned, a comprehensive meta-review in 2023 confirmed that exercise is efficacious in treating depression, with some analyses suggesting effect sizes as large as those of psychotherapy or medication. Aerobic exercise (like brisk walking, running), resistance training, and mind-body exercise (like yoga) all appear beneficial, with moderate intensity and group settings possibly maximizing adherence. Beyond symptom reduction, exercise improves sleep, increases brain-derived neurotrophic factor (promoting neuroplasticity), and can give a sense of accomplishment and routine. In integrated treatment plans, exercise is often “prescribed” alongside therapy and medication. For anxiety, regular aerobic activity has an anxiolytic effect via reducing baseline muscle tension and regulating neurotransmitters. Clinicians often encourage patients to see exercise as part of self-care just like taking a pill – with the patient tracking mood changes alongside workout frequency. Nutrition and gut health also come into play: a healthy diet can support better mental health (e.g. there is emerging evidence that Mediterranean-style diets rich in omega-3s can modestly reduce depression, and that the gut microbiome – influenced by diet – might affect anxiety). For IBS, dietary adjustments (like reducing gas-producing carbs) combined with stress reduction works best, underscoring an integrative approach.

Body-centered psychotherapy: Some modalities directly use movement, posture, or touch in psychotherapy (with proper ethical boundaries and consent). For example, Dance/Movement Therapy allows clients to express and work through emotions via bodily movement, useful for those who struggle with verbal expression. Alexander Technique or Feldenkrais Method (educational systems rather than therapies per se) teach awareness of body alignment and tension habits, which can relieve chronic pain and also increase emotional well-being (because chronic pain often coexists with depression/anxiety). In cases of severe dissociation (often from trauma), helping the person reinhabit their body safely is crucial – grounding techniques like feeling one’s feet on the floor, noting physical sensations, can reduce dissociative episodes. Therapists might guide a client to notice where in the body they feel an emotion (e.g. anxiety as a knot in the stomach) to facilitate processing it rather than fleeing it.

Overall, the somatic perspective fills an important gap: it addresses the fact that we experience and store emotions in the body and that the body can be a direct pathway to healing. Its evidence ranges from strong (exercise, certain mind-body therapies) to emerging (somatic trauma therapies). Integrating it ensures we treat the whole person. For example, a client with panic disorder might benefit from cognitive techniques to challenge catastrophic thoughts, and from learning to physically calm their autonomic surges through breathing – the combination is more effective than either alone. Or a client with depression might talk through their guilt and also be supported to gradually re-engage their body via movement, which can lift lethargy. Importantly, attention to somatic factors also means we consider physical health contributors: ruling out thyroid issues, ensuring adequate sleep, etc., which is part of integrated care (collaboration between mental health professionals and primary care).

One caution with somatic approaches is to maintain a trauma-informed, client-consent framework – some trauma survivors feel unsafe with body-focused exercises initially, so pacing is key. Also, not every client is interested in “alternative” techniques, so offering options and explaining rationale (e.g. “We know that when we slow our breathing, it sends a signal of safety to the brain; would you be open to trying a breathing exercise when anxiety spikes?”) is important.

Figure 2 (Appendix): Gut–Brain Axis Communication. The diagram illustrates how signals travel between the gut and brain through the vagus nerve (blue arrow, top) and bloodstream (bottom), involving the autonomic nervous system, HPA axis, immune and endocrine pathways. Mental stress can alter gut function (“butterflies” or IBS flare), while gut inflammation or dysbiosis can influence mood. Integrative treatment for IBS addresses both ends of this axis – for instance, dietary changes for gut health and cognitive-behavioral strategies to manage stress responses – leading to better outcomes.

Insights from Eastern Philosophies

Eastern philosophical and spiritual traditions (such as Buddhism, Taoism, and Hindu-Yogic philosophy) have long addressed mind-body integration and existential questions of suffering, self, and meaning. In recent decades, Western psychology has increasingly dialogued with these traditions, giving rise to interventions like mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR), mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT), and acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT), which explicitly draw on Eastern concepts. Key insights include:

Mindfulness and acceptance (Buddhism): Buddhism offers the concept of mindfulness – a focused, nonjudgmental awareness of the present moment – as a means to alleviate suffering. It also teaches acceptance of impermanence (anicca) and the idea that attachment to transient things causes suffering (the Second Noble Truth). These ideas align well with psychological principles: for example, panic disorder often involves fear of the body sensations of anxiety; mindfulness training helps individuals observe these sensations with curiosity rather than panic, which actually allows the wave of sensation to pass without escalating. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (though developed in the West) uses a strategy very resonant with Buddhism – encouraging acceptance of what is out of personal control (including uncomfortable feelings) and commitment to valued actions. This is almost a rewording of the serenity prayer or the Buddhist approach of radical acceptance combined with wise effort. Empirical evidence for mindfulness-based interventions is robust: MBCT significantly reduces relapse risk in recurrent depression (particularly effective for those with 3+ episodes, shown in multiple trials), and mindfulness practices reduce anxiety, chronic pain, and even help in borderline personality (DBT includes mindfulness as a core skill). The mechanism is partly via attentional retraining and reducing ruminative, judgmental thinking.

Buddhism also addresses existential suffering directly. The concept of dukkha (often translated as suffering or unsatisfactoriness) acknowledges that life inherently involves suffering (illness, aging, death, loss) – similar to existentialists’ recognition of life’s painful givens. The Buddhist path (Eightfold Path) provides a practical roadmap (ethical living, mental discipline, wisdom) to reduce self-created suffering by letting go of attachment and aversion. In therapy, this might translate to helping a client release attachment to fantasies (e.g. “I must have everyone’s approval” – causing endless anxiety) and cultivating equanimity. Non-attachment doesn’t mean indifference, but rather engagement without clinging – which can drastically reduce anxiety about loss or change.

Another Buddhist insight is no-self (anatta) – the notion that the self is not a fixed, independent entity, but a process, always changing. While this can seem abstract, it has therapeutic value: rigid self-concepts (“I am a failure”, or even “I am my trauma”) can keep people stuck. Recognizing the fluidity of self (that who I am is not defined solely by my past or labels, and can change from moment to moment) can be freeing. It also challenges narcissistic tendencies by showing the interdependence of all beings (countering a grandiose or isolated self-image). Some advanced mindfulness practitioners report a dissolution of the ego boundary in meditation, resulting in a profound sense of connection – this correlates with increases in compassion and decreases in narcissistic traits potentially, though research here is nascent.

Balance and flow (Taoism): Taoist philosophy from China emphasizes living in harmony with the Tao (the way of nature). It values balance (yin and yang) and the concept of wu wei (effortless action) – meaning acting in alignment with the natural flow of things rather than forcing. In psychological terms, this advocates for flexibility and adaptation. Many stresses arise from fighting reality (insisting things be a certain way) or overcontrol. Taoism would encourage a kind of cognitive flexibility akin to ACT’s “creative hopelessness” – recognizing where struggling against what is only causes more pain, and learning to ride the wave instead of clinging or suppressing. For someone with high anxiety, adopting a Taoist mindset might involve trusting the process of life more, loosening perfectionistic control, and practicing yielding in situations beyond one’s control. This can reduce anxiety and anger. Tai Chi, a movement practice rooted in Taoism, exemplifies these principles physically (soft movements redirecting force, balance between activity and stillness), and has been shown to reduce depression and anxiety in some studies – likely via both exercise effects and the meditative, balancing aspect.

Self-transcendence and karma yoga (Hindu philosophy): The idea of self-transcendence (rising above self-interest to connect with the greater whole) is also present in Hindu philosophy and yoga. The Bhagavad Gita, for instance, teaches acting without attachment to fruits – doing one’s duty for the greater good (karma yoga). This resonates with Frankl’s concept of finding meaning through self-transcendence. Encouraging clients to engage in altruistic or community activities can help lift depression (studies on volunteering show improved mental health for the volunteer). It also combats narcissistic preoccupation by focusing on others. The Gita also addresses existential despair – Arjuna’s crisis on the battlefield is met with Krishna’s counsel on duty, devotion, and seeing beyond the temporary. In therapy, when someone says “what’s the point of it all?”, different cultural lenses like these can provide alternative narratives (for a Hindu client, framing their struggle in terms of dharma (duty) and personal growth over lifetimes might resonate; for a secular client, one might talk about the legacy they want to leave or their contribution to humanity).

Holistic health systems: Traditional Eastern medicine (Ayurveda in India, Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM)) have always treated mind and body as connected. Ayurveda, for example, links mental states with bodily doshas and prescribes dietary, herbal, yoga, and meditative treatments to restore balance. TCM identifies patterns like Liver Qi Stagnation for depression-like symptoms and treats with acupuncture, herbs, exercises like Qigong. Some of these practices (acupuncture, for instance) have made their way into Western integrative medicine with some evidence for benefits in anxiety and depression (acupuncture often shows similar efficacy to counseling for mild-moderate depression in studies, though mechanisms are debated). While this report focuses on psychological and behavioral interventions, these ancient systems underscore the importance of balance, routine, and harmony – principles now reflected in Western self-care recommendations (sleep hygiene, balanced diet, stress management all echo these ideas).

In integrative therapy, Eastern insights often enter through secular techniques like mindfulness meditation, yoga, breathing exercises, or philosophical discussion if the client is inclined. It’s important to align with the client’s belief system – e.g., using Buddhist-informed approaches with a devout Christian might be reframed in their religious language (mindfulness can be taught as contemplative prayer or paying attention to God’s creation, etc.). The goal is not to impose a different culture’s worldview, but to enrich the toolkit with practices that have proven effective across cultures. Many clients appreciate learning these, as it gives them lifelong skills (a mindfulness practice is free and portable anywhere).

Empirically, many Eastern-derived practices have solid evidence (mindfulness, yoga, tai chi as mentioned). There is also emerging research on psychedelic therapy (not exactly Eastern, but some psychedelics like psilocybin reliably induce mystical-type experiences reminiscent of Eastern spiritual experiences of unity). Trials of psilocybin-assisted therapy for depression and end-of-life distress have shown large effect sizes, apparently because the intense experience often leads to a changed perspective on self and life – essentially an existential shift where people feel more connected and find renewed meaning. This is cutting-edge and experimental (with ethical and legal complexities), but it highlights that spiritual or transcendent experiences can have therapeutic value, an area Eastern traditions have cultivated for millennia via meditation, fasting, rituals, etc.

In conclusion, Eastern philosophies contribute the importance of mindfulness, acceptance, balance, and self-transcendence to the integrated framework. They provide time-tested methods to cultivate inner peace and resilience. Integrating them does not mean adopting any religious doctrine, but rather using their universal principles in a client-centric way. For example, a practical integration could be: a therapy session starts with a 5-minute mindfulness breathing exercise (Buddhist influence) to center the client; then proceeds to CBT work on their thoughts; later, the therapist uses an analogy of yin-yang to help the client accept both light and dark parts of themselves (Taoist metaphor for integrating the self); and ends with assigning a homework of a 10-minute walking meditation outdoors daily. This blend can greatly enhance the efficacy of therapy by engaging the client on multiple levels – cognitive, emotional, somatic, and spiritual.

Having established these theoretical foundations, we can see that each perspective offers distinct but complementary insights. Clinical neuroscience grounds us in the physical reality of the brain and body, cognitive-behavioral models give pragmatic tools to change maladaptive patterns, psychodynamic theory ensures depth and attention to the personal narrative, existential psychology brings in the issues of meaning and values, and somatic approaches engage the bodily dimension of emotions and stress. Eastern philosophies weave through, reminding us of mindfulness and balance. The next section will present an integrated framework synthesizing these into a coherent approach, before we apply it to specific conditions.

Toward an Integrated Neuropsychological-Existential Framework

Integrating the above perspectives is not simply a matter of using them in parallel, but of uniting them under a cohesive conceptual model of how mental health problems develop and heal. One useful unifying model that has gained traction is the biopsychosocial model, originally proposed by George Engel in 1977, which argues that biological, psychological, and social factors are all essential in understanding health and illness. Our integrated framework can be seen as an expanded biopsychosocial model – essentially biopsychosocial-spiritual or biopsychosocial-existential. This expanded model acknowledges an additional dimension: the realm of meaning, purpose, and values (sometimes termed the “noetic” dimension after Frankl, or “spiritual” broadly construed, not necessarily religious). Leading health organizations implicitly endorse this holistic view: the WHO definition of mental health includes realizing one’s abilities and contributing to community (value-laden concepts), and calls for integrated care across sectors. The American Psychological Association also encourages integrated care and recognizes the role of factors like religion/spirituality and culture in mental well-being.

Conceptual diagram (textual): We can imagine a person at the center of several concentric circles or intersecting domains:

- Biological domain: genes, brain circuitry, neurochemistry, hormones, physical health status.

- Psychological domain: thoughts, emotions, behaviors, skills, coping style, personality traits.

- Social domain: relationships (attachment style, family dynamics, social support), cultural background, socio-economic factors, life events.

- Existential domain: core values, sense of meaning, goals, spiritual beliefs, identity and self-concept, outlook on life (hope vs. despair).

A disturbance in mental health (say depression) typically involves factors in all domains: perhaps a genetic predisposition and inflammation (biological), perfectionistic thinking (psychological), recent divorce (social loss), and existential crisis (“who am I without my spouse?”). These factors interact – the existential crisis can lead to biological stress response (HPA activation), or the social loss can breed negative thinking, etc. No single domain alone explains or can fully treat the condition, but together, they do. The integrated framework thus calls for assessment and intervention at all levels.

Key principles of the integrated framework:

Multi-dimensional assessment: Clinicians should assess patients holistically. For example, in an intake for anxiety, one would evaluate medical contributors (e.g. hyperthyroidism), ask about cognitive patterns (worries, panic triggers), inquire about childhood or past traumas (psychodynamic history), gauge social context (support system, work stressors), and explore existential factors (what does the person most fear losing? what gives them a sense of security or meaning?). Standardized tools can aid this (there are scales for spiritual well-being, childhood adversity, social support, etc., which can be as important as symptom checklists). Through this comprehensive lens, one might discover, say, that a patient’s panic attacks started after the death of a close friend – indicating unresolved grief (existential loss) is a key piece alongside any biological propensity.

Interdisciplinary treatment planning: The treatment team or approach should address each relevant domain. This doesn’t always mean a specialist for each (which would be ideal but not always feasible); often a well-trained therapist can cover psychological and existential work, a primary care or psychiatrist covers biological interventions, and group therapy or family therapy covers social support. In integrated clinics (which are becoming more common), you might literally have a multidisciplinary team: e.g., a psychiatrist, a psychologist, a social worker, maybe a yoga therapist or chaplain – all collaborating on the case. When not co-located, coordination (with patient consent) is key, so that, for instance, the therapist and the prescriber communicate about progress and goals. The plan should be personalized: two depressed patients might have completely different integrated plans depending on their profile (one gets an SSRI + CBT + volunteering activity; another gets psychotherapy focusing on trauma + exercise + pastoral counseling for spiritual doubts, etc.).